A new simple benchmark for quantum computers

Run and measure a random quantum circuit many times and count the number of repeated outcomes. That’s it.

This blog post is an introduction to the recent arXiv preprint1: Counting collisions in random circuit sampling for benchmarking quantum computers, arXiv:2312.04222. In this paper we introduce a new method to measure the performance of current quantum computers that may be quite useful for monitoring and tracking the ongoing progress in quantum technologies.

Random circuit sampling

Random circuit sampling is a particular quantum computing protocol in which a given random quantum circuit C is applied to n qubits initialized in the |0⟩ state and a final measurement is performed in the computational basis (if you are not familiar with a quantum circuit, you can imagine it as the simplest program for a quantum computer, similar to a list of instructions). The result is a bitstring which looks quite random. For example, for 16 qubits, a possible result could be something like this:

0101100100010010.

If we repeat the procedure N times, we’ll get N measurement shots and therefore N classical bitstrings. Something like:

b1 = 0110110110001100,

b2 = 1100010100111110,

…

bN = 1101001101010001.

The measured bitstrings look quite random, as if they were sampled from the uniform distribution over all the D=2n possible outcomes. However, this is actually not true! In fact, if the quantum circuit is sufficiently random, i.e., if it prepares some pure state |ψ⟩ which does not have any preferred orientation in the Hilbert space (Haar-random), the probability distribution of the possible measurement outcomes is not uniform. In practice, for a typical random state |ψ⟩, some bitstrings are slightly more likely than other bitstrings. This is a statistical property of random quantum states2.

This effect is true for a “good” quantum computer having a sufficiently low level of noise. The more the computer is noisy, the more the distribution of the measurement outcomes becomes uniform. In the high-noise limit, the outcomes become uniformly distributed and the quantum computer behaves as a trivial classical random number generator. This fact can be turned into rigorous operational benchmarks such as the cross-entropy benchmark 2 3 or the quantum volume4. Unfortunately, these methods require the classical computation of the ideal noiseless probabilities of all the possible bitstrings or, at least, of all the measured samples. In other words, it is possible to quantitatively distinguish quantum samples from uniform samples, but you have to pay a classical computing cost which scales exponentially in n.

A quantum-only approach based on collisions

Is it possible to distinguish quantum samples from trivial uniform samples without using any classical computing? In our recent work1, we show that counting the number of repeated bitstrings (also called collisions in statistics) can be a very straightforward way of doing it. Indeed, it turns out that samples obtained from a pure random state tend to have more collisions with respect to samples drawn from the uniform distribution.

Basically, all we need to do to verify that a quantum computer is behaving in a “quantum” way is running a random quantum circuit many times and checking if the number of re-sampled bitstrings is larger than the expected number of collisions for the uniform distribution.

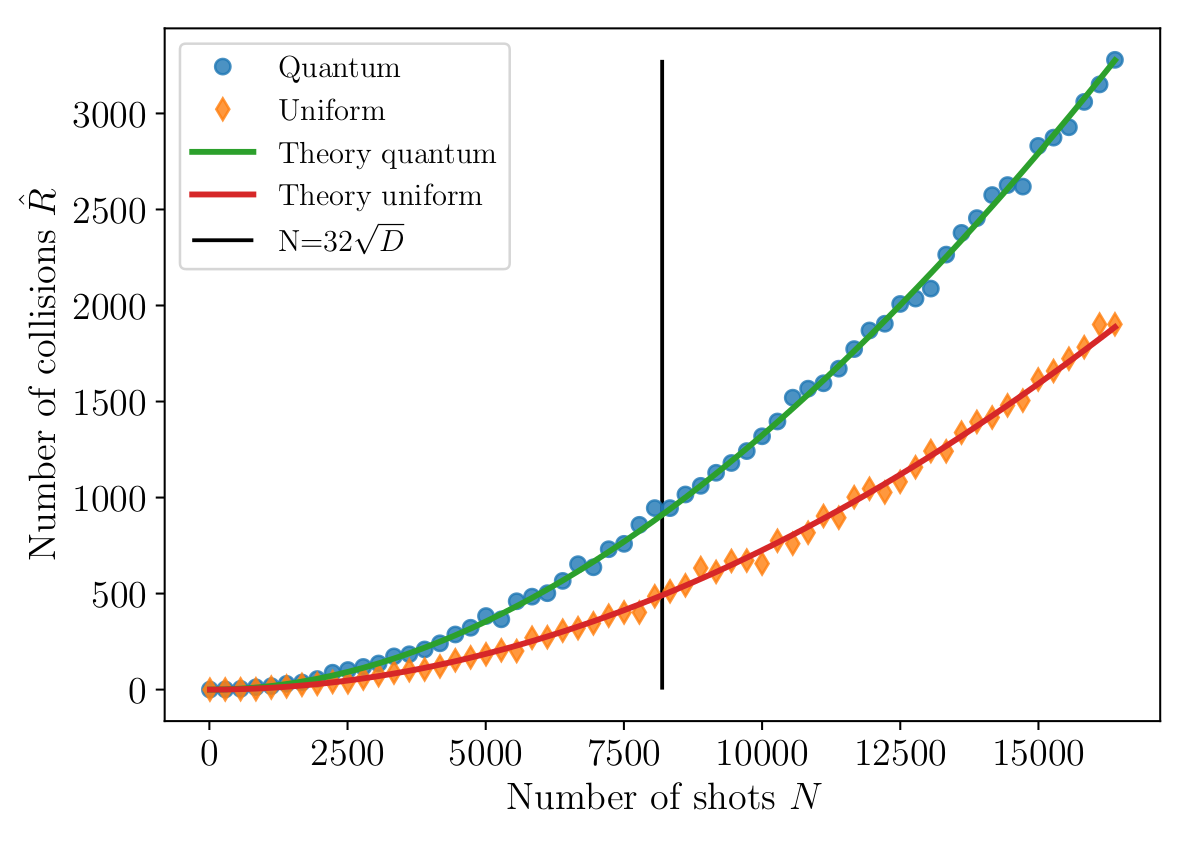

For example, when measuring a random state of n=16 qubits with N=104 shots, the expected number of collisions is ≃1324. For the uniform distribution over 216 bitstrings instead, the expected number of collisions in N samples is ≃726. The below figure, extracted from the paper, is a numerical simulation of the number of observed collisions for different values of N.

This phenomenon is not very surprising: if for a pure random state some bitstrings are more likely than others, it means that they tend to get re-sampled more frequently. This effect can be easily turned into a quantitative benchmark for the performance of a quantum computer, via a simple function of the number of collisions observed when sampling a random circuit. Specifically, in our work we introduce two quantitative benchmarks: the collision anomaly and the quantum collision volume. Moreover we also propose a method to cross-validate two different quantum computers by counting the number of cross-collisions in their measurement outcomes. More technical details can be found in the paper1.

Sampling cost and the birthday paradox

The new bechmarks based on the number of collisions have basically zero classical computing cost. Unfortunately, they have a large quantum sampling cost. In fact, in order to observe some collision events, one needs to collect at least N= 𝓞(2n/2)= 𝓞(√D) samples. This is an exponential scaling with respect to the number of qubits. In other words, the exponential classical cost, typical of the cross-entropy and quantum volume benchmarks, is now transformed into an exponential sampling cost.

We note however that, thanks to the square root scaling in D, the number 2n/2 =√D is much smaller than the dimension of the Hilbert space (D=2n). For the uniform distribution, such square root reduction of the sampling cost is also known as the birthday paradox: even if there are 365 days in a year, a small group of just 23 random people is enough to have a 50% probability of a shared birthday. It is interesting to note that the same kind of “apparent” paradox is what makes our collision-based benchmarks practically feasible for near-term quantum computers, despite the asymptotic exponential scaling in n.

Footnotes

-

Andrea Mari, Counting collisions in random circuit sampling for benchmarking quantum computers, arXiv preprint (2023) arXiv:2312.04222. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Sergio Boixo, Sergei V Isakov, Vadim N Smelyanskiy, Ryan Babbush, Nan Ding, Zhang Jiang, Michael J Bremner, John M Martinis, and Hartmut Neven. Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices. Nature Physics, 14(6):595–600, (2018), arXiv:1608.00263. ↩ ↩2

-

Scott Aaronson and Sam Gunn. On the classical hardness of spoofing linear cross-entropy benchmarking, arXiv preprint (2019), arXiv:1910.12085. ↩

-

Andrew W Cross, Lev S Bishop, Sarah Sheldon, Paul D Nation, and Jay M Gambetta. Validating quantum computers using randomized model circuits. Physical Review A, 100(3):032328, (2019), arXiv:1811.12926. ↩